I am not sure if I have a yarn stash or a yarn infestation.

But I do have a working theory as to where yarn comes from.

Abstract:

Yarn is actually garment larvae. I can prove this with these never-before seen photos of actual wool garments in full mating display. In the following photo, we can see the colorful male garment showing off his size and prowess while the less brightly plumaged female exhibits her willingness to copulate by lounging seductively and emitting wool pheromones:

In the second photo, the pair has been captured in the act of mating:

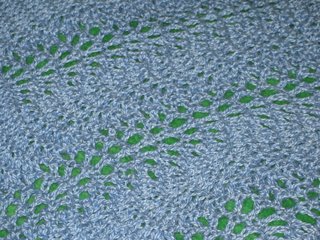

During gestation, the female hides in a dark closet until the eggs are ready to be laid, when she will seek out a suitable nesting site. The following photo shows a green-skinned subspecies in the egg-laying stage. She everts her highly elastic cloaca to allow a new skein of mauve-colored yarn to enter the world:

In selecting a nesting site, females tend to prefer empty plastic bags, boxes, bins, dresser drawers or baskets, with Rubbermaid tubs being preferred above all other nesting materials. However, in a pinch, females have been known to deposit eggs in coffee cans, backpacks, unused punchbowls, and luggage. In short, anyplace dark and quiet which isn't disturbed very often makes a good nesting spot.

Sometimes the same nest will contain eggs, larvae and pupae in several stages of development. My research team believes that the females, who are constantly in heat and who remain continuously fertile, return repeatedly to the same nesting spot over a period of time.

In the following photo, you will see a new "skein" -- the earliest developmental stage -- of bright green wool , freshly laid directly on top of several larvae in the "ball" stage. Apparently this female has mated with several different males, as determined by the variety of colors in this clutch:

Migrating females often select retail shops to deposit large clutches of eggs. Just as many birds often share the same nesting grounds, fiberologists believe that multiple nests of varied garment subspecies help assure the overall survival of the genus.

The female will lay anywhere from a single egg to hundreds. Eggs may closely resemble the adults of their species both in color and in texture, or they may vary wildly. The eggs can incubate anywhere from a few hours to several years before they enter the pupal stage and begin to make their chorus of faint, monotonous, but unmistakable maturity calls, which sound like:

"...nit-meee, nit-meee, nit-meee ..."

The persistent, low call attracts the species Lana knitterati, otherwise known as the common knitter, a species found in most parts of the world, who assist the garment larvae out of the pupal stage and through the metamorphosis into an adult garment. Most fiberologists believe that the repetitive motion of the knitter's hands actually plays a vital role in the metamorphosis from larvae to adult.

Lana knitterati are commonly found wherever sheep, llamas, silkworms, cotton, or garment larvae are present. The species originated in Central Asia, but due to human imperialism and the opening of trade routes and shipping lanes, these creatures have invaded every part of the planet, much in the same manner as domestic cats, the common house sparrow and Rattus rattus.

Subspecies include L. knitterati norvegicus, known for its striking geometric color patterns and L. knitterati gaelicus, a subspecies containing two major races: L. k. gaelicus aranii, easily recognized by the bold texture if its skin, and L. k. gaelicus fairisleii, which, although bearing strong color markings, can be distinguised from the norvegicus subspecies by repetitive X- and O-shaped markings within prominent color bands encircling the torso. Like most isolated island species with a common ancestor, several other races of L. k. gaelicus have developed, including the races of ganseyii and faroeseii.

May other subspecies exist throughout the world: a color-patterned variety known as intarsius, many races of laceii, and highly prolific strains of sockus, mittenus, and scarfus, which are considered invasive species in most parts of their range.

Among the laceii races, most fiberologists consider the sighting or capture of the rare orenbergus to be the field experience of a lifetime.

Many questions in the natural history of yarn remain unanswered by science -- especially the mysterious, and alarmingly frequent, tendency of garment pupae to simply stop development partly through the metamorphic process and to remain in stasis for indefinite periods of time. Sometimes, adult garment development spontaneously resumes after many weeks or years of stasis, but in many sad cases, development ceases entirely. Sometimes, the common knitter becomes involved at this stage -- in a magnificent display of Nature's abhorrence of waste, scavenging knitters actually unravel the partly-developed pupae. We continue to study this phenomenon.

These remarkable photographs remind us again of the interdependence of all species. Just as certain rainforest flowers have evolved so that they can only be pollinated by a single species of hummingbird ... yarn larvae could never develop into adult garments without the assitance of Lana knitterati, the common knitter.-- Dr. Mambocat, PhD, BsFD, KD

Note to class: the next time Fiberology 101 meets, we will futher discuss the interdependence of yarn and garments with other species.